Day 260 - Introduction to the American Wing

August 12, 2021

Barbara Gewirtz told me that when she was a kid, her favorite galleries in the Met were the period rooms. Certainly, the 18th century French rooms are among my least favorite spaces, but I thought I might have a different reaction to the American period rooms, which I assume will be less grandiose and ornate. Unfortunately, I suspect it will be quite a while before I can test that reaction and that assumption, since it turns out that most of the American period rooms are closed, whether because of Covid or because they are undergoing renovation (or a combination) I'm not sure.

I spent quite a while looking for the next open gallery in the numerical sequence and finally hit on gallery 723, a space behind the facade of the Second Bank of the United States. A placard in the gallery, bearing the title "Welcome to the American Wing," really should be placed at every entrance into the wing. It explains that the wing was established in 1924 and initially focused on European-American decorative arts from the Colonial and Federal periods. Since then, the collection has expanded to include Native American arts and a variety of objects made by African American and Latino artists as well.

Gallery 723, a grand space perhaps 40 feet by 30 feet, exemplifies this broadening of scope (and presumably of the museum's larger mission). The furnishings are those of the Federal period (1790-1810). They are relatively simple in form, with clean lines. A number of pieces have lavish veneers, a way of adding an elaborate and elegant, but not fussy, decorative note. One thing I should have known but didn't: Sheraton and Hepplewhite, whose furniture designs were so popular and widely adopted in the United States, were both English.

I particularly like a set of eight side chairs made in New York City between 1810 and 1820 of mahogany and yellow cedar. Their lyre-shaped backs especially appeal because of the references to classical art and to music. The chairs are arranged around a large dining room table with two leaves made of the same woods and dating from the same time period I wonder whether the table and chairs were at one point owned by the same family. I note that they were donated to the museum by different donors - but were the donors related? The chairs were a gift of the family of Mr. and Mrs. Andrew Varick Stout. The Varicks have got to be one of the oldest families in New York, with a street named after them that's most familiar to us as the headquarters of the city's Board of Elections.

What I respond to most, however, are two paintings that are very similar in format, perhaps 30 inches high and 26 inches wide, and that serve as emblems of the museum's commitment to a more diverse collection. The first is a 1786 portrait by Gilbert Stuart, executed in oil on canvas, of the Mohawk chief Thayendanegea, known as Joseph Brant. Interestingly, the portrait was commissioned by Hugh, Earl Percy; the placard notes that "the two had met while commanding allied troops during the American Revolution." This made me wonder: Did they both fight on the British side? I looked up Percy first, then Brant (I'm not proud of the order of these inquiries), and the answer is yes! Percy played a critical role in the Battles of Lexington and Concord but subsequently resigned his commission because of disagreements with General Howe. And, although most Mohawk tribes supported the colonists, Thayendanegea was an exception. Nonetheless, according to the signage, he was one of the best known and respected Native Americans of his generation and lobbied for his people with both King George III and George Washington.

Stuart paints his subject in three-quarter view against a light background that presumably evokes the sky.I initially guessed that the chief was in his early 40s, and it turns out I'm right - he was 43! (A certain slackness in the jaw....) It's a compelling image: Thayendanegea looks thoughtful, intelligent, certainly sober and perhaps sad, as if he were contemplating a distressing future for his people. I am not sure what his garb represents - a Native American headdress, no doubt, but what about the metal neckpiece?

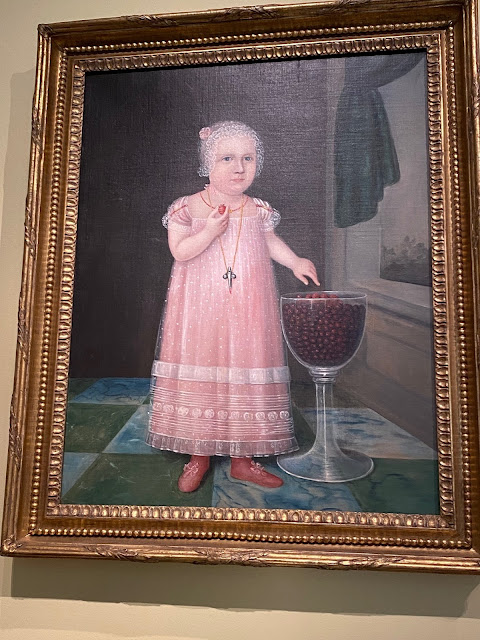

The second painting is an 1805 portrait of a Maryland child, Emma Van Name, by Joshua Johnson, the earliest known African American painter to earn a living from his art. The son of a white father and an enslaved mother, he secured his freedom and landed many commissions from members of upper-class, white Baltimore's society. The sign describes the painting as "an icon of American folk painting." While the rather odd scale of the girl's figure and her placement next to a huge goblet of strawberries give the painting a decidedly folk art quality, I admire the skill with which Johnson painted the girl's attire, which appears to consist of a sheer dotted layer over a pink undergarment and a lacy cap.

Comments

Post a Comment